In Derivatives, Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan contemplate the materiality of their own works involving large-scale installations produced with communities and other collaborators. It bears the pondering that accompanies an incredible body of work spanning decades across different site-specific projects and a multitude of locations. From these different spaces and engagements with various artists and volunteers, a timely reflection comes to the forefront at this stage in their career—on whether value can be derived from the process or the final object; on whether the work’s significance lies within the ephemera or its permanence.

This derivation involves the memory of forms, processes, and concepts. It also involves the encapsulation of events—interactions that took place and the collaborations that shaped the objects. In essence, it is a memorialization. As their practice has continually sought the participation of the communities that surround them, most of the materials they have used are built from recyclables and through ad hoc constructions. Most are contributions and repurposed belongings—in particular, the cardboard boxes around which their practice has revolved.

To transform impermanence into something firm and lasting stands as a testament to the different hands that worked on past projects, as well as to the diverse ideas conceived about settlements, displacements, migrations, and journeys. Their new forms—turned into metal sculptures—act as a compendium and archive of the situations the Aquilizans have immersed themselves in. True to their lifelong involvement with other craftsmen, these metalworks are sourced from a community of farmers in Pililla, Rizal, where they conducted their own metalsmith workshops to help alleviate the dry seasons for harvest.

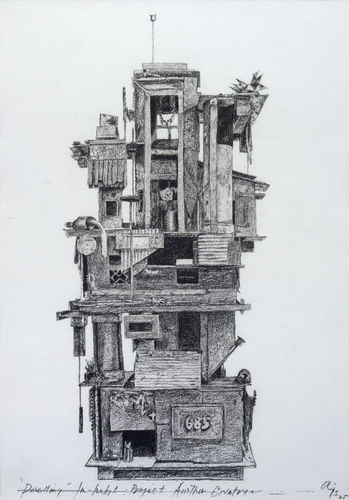

There is a strange familiarity when we suddenly see the iconic cardboard sculptures turned into stainless steel. Although smaller in scale, they still remind us of the intricacy and—even the frailty—of their original forms. They exude a lingering presence from the once massive assembly. It attends to a kind of commemoration, of redoing the processes of construction—this time more deliberate and exacting as it deals with a more vigorous material. Most of the derivations come in the form of shanties or makeshift houses, emerging vertically as a reflection of Filipino resourcefulness, which is a steadfast motif in the Aquilizans’ persistent redefining of ‘home.’

The charcoal drawings enact the process of re-creation on paper. Serving as record or facsimile, the depiction of sculpture as image allows both artists and audiences to meditate on its appearance, as well as on the memories of its making. The act of drawing is also an act of transforming these ideas into space—a more archival space like paper—and it surpasses the notion of mere reiterations when both collective memory and artistic process are put into question: which should serve the purposes of art-making?

The ‘derivative’ here is not an instance of mere duplication, but it does celebrate the copy. It is a process of re-enactment, and at the same time, a critique of the whole idea of resampling and repurposing— concepts that are often critical in their own right when it comes to the nature of art and originality. In a way, Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan use this critical moment to continue their aspirations of redefining the complex nature of finding and establishing home and identity. And it is through these new variations of forms and materials—where the past forms are enshrined, documented, remembered, or, to say the least, examined as a process for belonging—as they try to find their place in the world of art objects.

/CLJ